(published on june 19, 2023)

“내 손톱이 빠져 나가고, 내 귀와 코가 잘리고, 내 손과 다리가 부러져도 그 고통은 이길 수 있사오나, 나라를 잃어버린 그 고통만은 견딜 수가 없습니다. <중략> 나라에 바칠 목숨이 오직 하나밖에 없는 것만이 이 소녀의 유일한 슬픔입니다.”

“Even if my fingernails are torn out, my nose and ears are ripped apart, and my legs and arms are crushed, the pain of this body cannot be compared to the pain of losing my nation. My only regret is that I couldn’t do more than give my life for my country.”

– 유관순 / Ryu Gwan-soon

What can we learn from the past? How do we interpret such poignant and ruthless stories? How do we remain jubilant when the most wretched vessels of malice attempt to destroy our identities?

As people acquire and latch onto their revolutionary hope, art is inevitably and indubitably brought up as a channel for further optimism, love, and expression, utilizing its endless mediums to highlight our communities and aid in our organizing.

ID: A black and white photograph portrait of June Nho Ivers from Since I Been Down. She is looking towards the camera with a solemn expression, hair tied up back.

Our Iyagi was able to communicate with June Nho Ivers [she/her] (also known as Chu Ki Won) as she shared her experience with galvanizing community organization through art as a conduit for liberation. As a Korean diaspora with visceral recollections of familial stories passed on by preceding generations, Ivers was willing to allot such anecdotes to Our Iyagi, focusing on the overarching message of reunification and detailing into the specific medias utilized in her art exhibitions at the ‘ACES Symposium’ and Kasama Meryenda’s “Have you Eaten” Group Show in (so-called) ‘Seattle, Washington.’ Her film was additionally celebrated as the Best Experimental Short in the Korean International Short Film Festival.

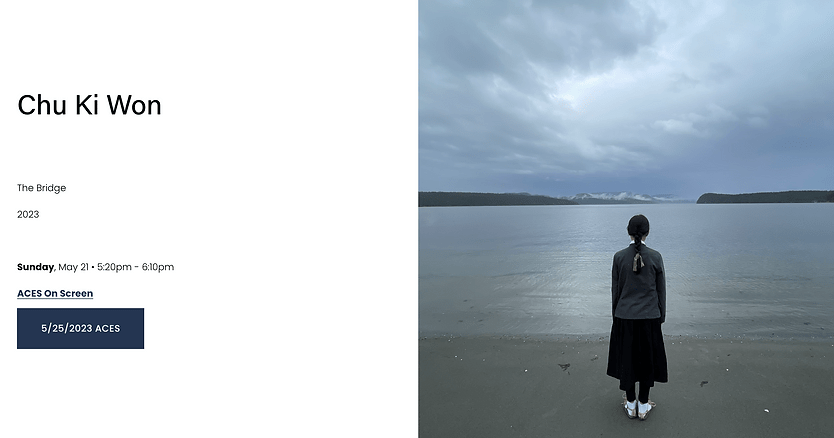

ID: An image of The Bridge showcase on Ivers’ website. There is a photograph to the right of the screen which shows a person (wearing a dark grey top and a black skirt) with their hair braided back, facing the waters in front of them.

Through questionnaires and conversations, Ivers opened up about how her life as a Korean woman and her nation’s history of struggle, devastation, and community-care have been vital motifs to her varying projects as a multimedia artist.

“As the third child, my mother would tell me stories about her life and family. Her maternal grandmother began an orphanage in Busan with the encouragement of Chu Ki Won…these stories of the lost uncle and aunt filled my imagination, and I began to create a file in my mind of these stories.”

Ivers continued on, elucidating how she grew up in an environment hostile and exclusionary to the history of colonized and disparaged Peoples. She details how she was the only Korean in a white-centered community, specifically being “the only ‘non-white’ kid until the fourth grade.”

“I excelled at Western art, culture, thought, language and history, but I realized I really knew nothing of myself and my own history. When I went to college, I took an Asian ‘American’ Diaspora [course], and the professor noted that I was the only student in the class that was a ‘transcontinental being’ because I was not tethered in any space.

I always felt like a stranger in a strange land. I can navigate spaces in Europe because I have a grasp of Spanish, French, Italian and German. I can navigate spaces in Asia because I can access spaces within my [own] identity, but I [still] sit at a barrier because I’m too ‘westernized.’”

Ivers continued on to explain her journey regarding how she connects with fellow creatives and implements such experiences into her work as an artist.

“[For] the sake of brevity, I will say that my journey as a creative has always been instilled in me. My family is greatly influenced by classical music as it was actually how my grandmother was able to come to ‘Chicago’ before 1968 as a music student. My mother studied piano when she left Korea at the age of 18.

Music led me to theater, and theater led me to filmmaking. I originally went to Northwestern as a Theater major but quickly transferred to Radio/Television/Film. After graduation, I went to ‘Los Angeles’ to work on music videos and commercials. My fundamental desire to ‘survive’ overcame my capacity to make art. It is not an industry for folks who have limited resources.”

ID: A black and white family archive of June Nho Iver’s relatives. There are nine people sitting and standing as they look towards the camera. Most with shaven or short hair.

It has been her priority, as a filmmaker, to always “create opportunities and places of grace for” communities who are held under white hegemony “and women folk.” Ivers stated how she “gave opportunities to folks whether it was background casting or mentoring other filmmakers, work[ing] with conscientious collaboration and uplift[ing] stories of” criminalized and repressed voices.

“It wasn’t until I worked on Since I Been Down, a documentary about education in the prison system in the ‘State of Washington,’ that I really thought about creating a piece about the Korean diaspora. In prison, there is a program called T.E.A.C.H. (TAKING EDUCATION AND CREATING HISTORY). They actually study history, our indigenous selves, and how that informs our identity in Western-dominant culture. In my own personal practice of [dissecting and humiliating] white supremacy, I’ve been exploring the[ese] concepts to create more art that is centered on Korean cultural [identity] and how it expands to [our] indigenous practices.”

Our Iyagi inquired Ivers if she had any Korean revolutionaries/artists who have cultivated her own knowledge in Korean history and the role in which art plays in organizing.

She began explicating her family history, specifically her great-grandfather and his life in relation to uprisings and peoples’ movements. . .

“My maternal great-grandfather was 주기원 (Chu Ki Won). From my understanding, based on Korean government documents and family lore, he was a pastor and organizer in the Mansee Movement / Sam il Jeol. The [movement’s] intention was a peaceful demonstration which resulted in a bloody massacre and suppression of the Korean people.

He was an aide to Kil Sun Joo 길선. From my understanding, he helped the 33 ministers that created the Korean Declaration of Independence from Colonizing-Japan. He was targeted by Japanese people and was even imprisoned under the accusation of an assassination attempt of Governor Teraauchi. From all accounts, he was a kind and noble man. I heard a story that he was also a part of the military and could ride a horse from Pyongyang to Seoul in one day. He was originally from Pyongyang, and during the time of the escalating conflict ‘between’ ‘north’ and ‘south’ Korea, the communists regarded him as a ‘hero’ and permitted him to keep property in ‘north’ Korea.”

She stated that he left ‘north’ Korea, but his wife, 박진실, and his family were unable to follow alongside him.

Ivers went on to detail why she even began creating films in the first place and how that connects to her own hopes for Re/unification:

“At a micro level, I want to carry the stories of my people to my children so that they are not untethered from their Korean identity as multi-racial children.

Towards the end of his life, my maternal grandfather, who worked as a community-organizer in ‘Chicago,’ made attempts to find his lost children in ‘north’ Korea. The trauma of the separation created a rift in the marriage, but we just accepted it.

I create art under the name of Chu Ki Won with a grandiose intention that, one day, it can create a connection to my lost relatives in ‘north’ Korea. I know it sounds lofty, but I do dream of reunification. I know that part of my identity is rich with my family history, and I fantasize that one day, I can hug the descendants of Chu Ki Won.”

Ultimately, June Ivers shared her own artist’s insight into how she utilizes such poignant yet optimistic motifs and familial bonds into her creative works and art installations:

“My aunt was 8 years old when she left ‘north’ Korea. She is the only living relative that I have that has a recollection of what life was like there and her tenuous journey leaving ‘north’ Korea.

This piece is a dream. It is to create an unreliable memory of the children and their struggle for survival in a time of trauma. The Korean people have collectively experienced trauma for almost a century. As I researched those who were orphaned by the war, I imagined what it would have been like if the children survived and if it was my aunt who was able to guide them.

We often misunderstand the resiliency of children. They are vulnerable, but they have power.

[Therefore,] it [truly] lies in the power of imagination and play. Children can survive trauma, but we often don’t know how to process it.

I dream of the children.”

—

Our Iyagi sends our deepest gratitude and care for June Nho Ivers and her willingness to share her background as an artist and detail on how her identity today dates back to the generations who came before her. And as she continues creating diverse frames of works, such as a documentary regarding the Korean-German diaspora of miners and nurses and an additional film exposing USDA loans and its impact on Hmong farmers, we are delighted to support her gripping creations as a community. If you would like to contact Ivers and/or support her work, you can find her through:

Film / Multi Arts – Chu Ki Won

If you would like to privately access her film (which was granted high recognition as the Best Experimental Short in the Korean International Short Films Festival), you can email her directly in order to view it as it is not available on the internet at this moment.

Email: contact@june-films.com

Music related

- folks can reach out to Ivers via june@psychobummer.com

- DJ Ajumma https://soundcloud.com/dj_ajumma

- including her conversation about Gisaeng to Kpop